The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines anger as a desire for revenge. However, before the time of Jesus, anger was not interpreted as necessarily negative.

Some stoic philosophers (e.g., Galen and Seneca) viewed anger as a weakness—and even a kind of madness–while Plato viewed it as one of the unruly passions undermining our rational soul.

Other philosophers saw anger in a more positive light. Aristotle, for example, considered anger a natural emotion arising from an injustice that seeks retribution. He further noted that anger is better than the sweetest honey when it achieves its just retribution.

The Sin of Anger in the Bible

The Old Testament views anger similarly to Aristotle and mostly addresses it in the context of Yahweh’s anger. Since Yahweh’s anger arises out of His moral will, it is always—and so also are the retribution and punishments that arise from it.

In the New Testament, Jesus supersedes the permissibility of righteous anger in the Old Testament, implying that God does not take vengeance on His enemies and, therefore, on our enemies.

Jesus intentionally links anger to the fifth commandment—the prohibition against killing— suggesting that anger is the interior attitude that gives rise to the most serious sin against our neighbor.

Literature throughout history offers a multitude of examples of anger superseding reason. Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” Shakespeare’s tragedy of “Hamlet,” and Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights” are prime demonstrations of the deathly consequences of unharnessed anger.

The Deadly Sin of Anger Blinds in Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’

W.H. Auden, in an essay on anger, writes, “Anger, even when it is sinful, has one virtue; it overcomes sloth.”

These words of Auden ring true in Dante’s personifications of the wrathful in his “Divine Comedy.” In hell, the angry dwell in the river Styx. Dante encounters them on his journey and describes the scene as follows:

And I, intent at looking as we passed,

Saw muddy people moving in that marsh,

All naked, with their faces scarred by rage.

They fought each other, not with hands alone,

But struck with head and chest and feet as well,

With teeth they tore each other limb from limb. -Inferno VII. 109-114

Dante explains that, as punishment for letting anger control them in their earthly life, anger now completely controls the wrathful and their movement in hell. Among the dead, anger is taken to its utmost level as violence towards another (since its victims are already dead), whereas among the living, anger is taken to its utmost level as murder (as Jesus taught).

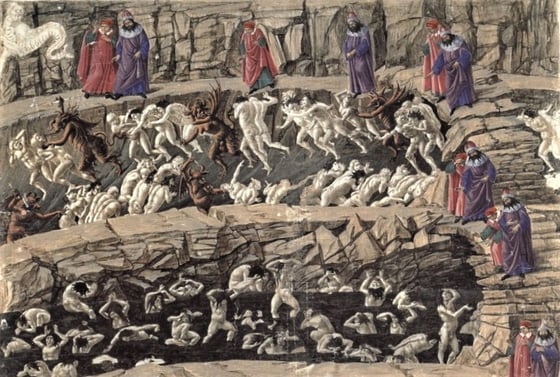

Dante's Inferno / Sandro Botticelli - Drawings for Dante´s Divine Comedy

Dante's Inferno / Sandro Botticelli - Drawings for Dante´s Divine ComedyDante further illustrates the nature of anger in the “Purgatorio.” Here, the angry souls dwell in a cloud of smoke, illustrating how anger clouds your judgment.

In “Purgatorio,” Dante uses examples of meekness, the opposite of anger, to purge angry souls. One example is the Virgin Mary and her treatment of Jesus once she found Him after looking for three days.

“A lady at the entrance whispering,

Tenderly as a mother would, “My son,

Why hast thou dealt with us this way?” -Purgatorio XV. 88-90

Mary’s gentle treatment of her Son contrasts with the harshness of anger. In the New Testament, Jesus does not ask us to repress our anger but to dispel it through radical forgiveness. Dante shows this in the “Purgatorio” with his example of the Holy Virgin and others.

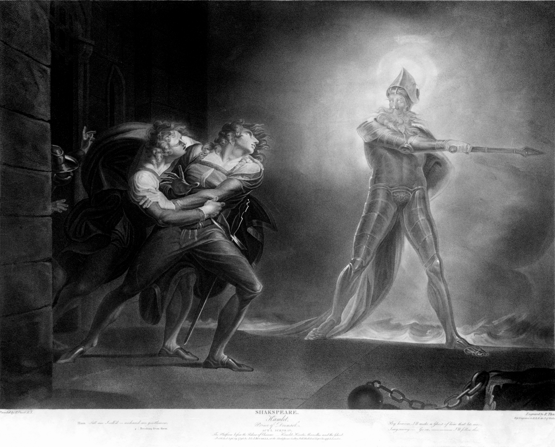

The Deadly Sin of Anger Leading to Death in 'Hamlet'

Auden again captures another essential aspect of anger with his words:

“The sin of anger is one of our reactions to any threat, not to our existence, but to our fancy that our existence is more important than the existence of anybody or anything else.” -W.H. Auden

In “Hamlet, Prince of Denmark,” Hamlet is guilty of thinking that his need for vengeance is more important than the existence of anything else. While Hamlet’s anger may be justified (as it springs from his uncle murdering his father), it brings immense ruin to Hamlet and everyone around him.

If Hamlet had let reason be in control, he would have seen the errors of his ways after mistakenly killing another man in place of his uncle. Instead, Hamlet continues to seek vengeance, and in turn, his mother, his betrothed, her brother, his uncle, and eventually himself all die.

Shakespeare’s tragedy validates the teaching of Jesus that anger, even when justified, frequently leads to needless pain, destruction, and death. Anger is a powerful and negative passion—whether justified or unjustified.

The Sin of Anger Depicted as Revenge in ‘Wuthering Heights’

Yet another quote from Auden perfectly captures the rage of the character of Heathcliff in Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights”:

“We wish to make others suffer, because we are impotent to relieve our own sufferings.” -W.H. Auden

Heathcliff lives his whole adult life as a series of revenge plots. An orphan child abused by his adopted brother Hindley, Heathcliff swears he will get revenge. At one point in the novel, he states: “I’m trying to settle how I shall pay Hindley back. I don’t care how long I wait, if I can only do it at last. I hope he will not die before I do”

Heathcliff with Cathy as portrayed in the 1939 film, "Wuthering Heights" starring Sir Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon

Heathcliff with Cathy as portrayed in the 1939 film, "Wuthering Heights" starring Sir Laurence Olivier and Merle OberonHowever, revenge towards Hindley is not the only vengeance Heathcliff wishes to render. The love of his life, Cathy, marries another man, Edgar Linton. To get back at Edgar, Heathcliff stops at nothing; he even goes so far as to marry Edgar’s sister, Isabella, to make her life miserable.

While Heathcliff’s revenge plots seemingly work out in his favor, he is eventually left with nothing. Anger’s stepchildren—hatred and vengeance—lead to madness and destructive consequences. This is most certainly true in the life of Heathcliff, who dies alone and unhappy.

Anger must be avoided at all costs unless one wants to end up like the wrathful in the “Inferno,” or Hamlet or Heathcliff. To avoid it, we must adopt the good habit and discipline of forgiveness and meekness to imitate Christ and his Mother.

*Originally published August 31, 2020.