In Part 1 of the Belief in the Brain Series, we saw that objective, material reality does not enter our consciousness in one complete image, but is derived from primary sense perceptions and the memories, thoughts, and emotions created by our brain’s association areas.

What can science tell us about the claims of mystics—made throughout the centuries—of experiencing contact with “God,” more accurately described for the purpose of Dr. Andrew Newberg’s research, as absolute unitary being?

Newberg lists several characteristics based on years of his own research and studying reports of mystics:

- Time and space are perceived as non-existent

- Normal rational thought processes give way to more intuitive ways of understanding.

- An experience of the presence of the sacred or the holy

- Perception of the essential meaning of things…resulting in ultimate freedom.

In other words, the most fundamental aspect of these experiences is the “compelling conviction that they have risen above material existence, and have spiritually united with the absolute.” (Newberg, p. 101)

It is reasonable, then, to ask the question: what can science tell us about these experiences of an absolute “non-material” reality?

The brain during a spiritual experience described

At the beginning of Newberg and Aquili’s book, the Tibetan meditators from the imaging studies describe the loss of a sense of self and of unity with everyone and everything. The Franciscan nuns who participated described it in slightly different terms: a tangible sense of God’s closeness and of union with Him.

So what part of our neural architecture lights up when this peak of the meditative experience occurs?

The posterior-superior parietal lobe—dubbed the Orientation Association Area (OAA) by Newberg—is responsible for defining an individual’s boundaries and keeps tabs of its orientation within the surrounding physical space. The activity within this area is constant—even at rest—and allows us to seamlessly interact with our environment, crucial for our survival.

What the SPECT images taken at the peak of meditation revealed was a decrease in the activity in the OAA—confirming a neurological state consistent with the experiences described by the participants. One loses the boundaries that define the self, so a feeling of union with all things makes sense.

These images hint at the basis—in a normally functioning brain—for the sense of transcending material existence and of connecting to an Absolute (or ultimate) Unitary Being as the authors call it later in the book.

In other words, the mind is mystical by default. We can’t definitely say why such capabilities have evolved, but we can find traces of their neurological roots in some basic structures and functions, primarily the autonomic nervous system, the limbic system, and in the brain’s complex analytical functions. (p. 48)

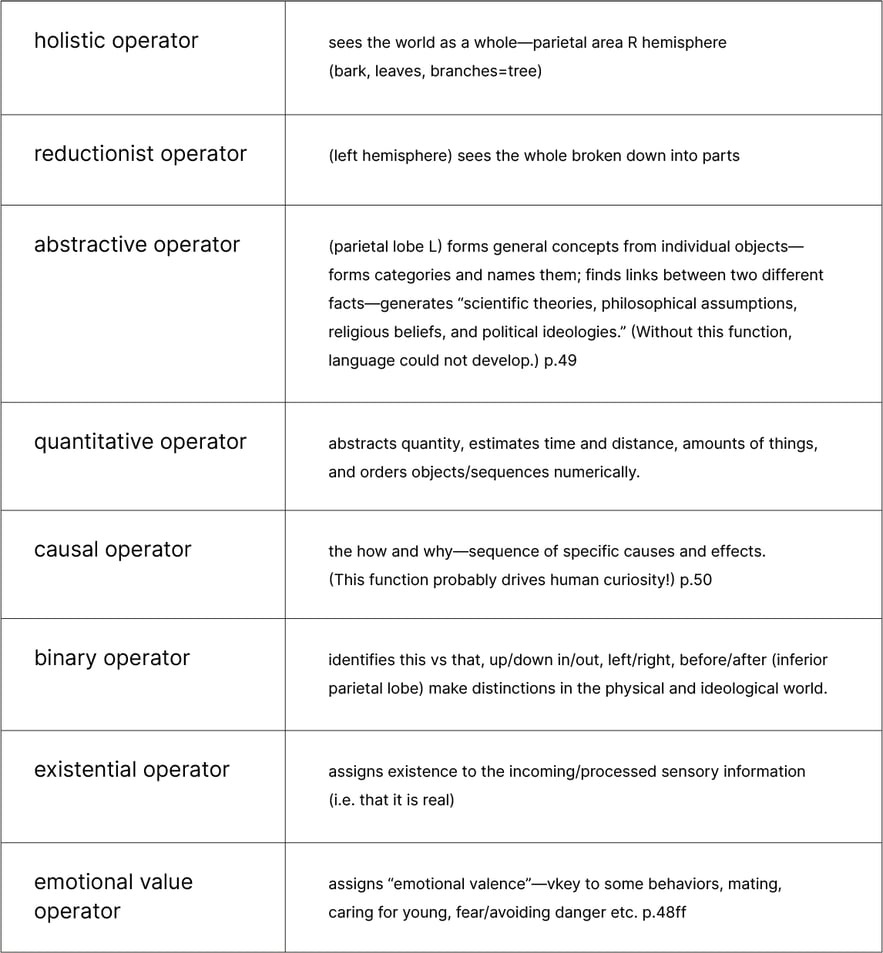

These analytical functions or ”cognitive operators” along with two autonomic “states” and the limbic system play distinct but overlapping roles in generating the religious experiences described by those who meditate, common experiences that transcend cultures, types of spirituality, and religions.

Spiritual experiences explained by the Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system is composed of two complementary branches: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. Sympathetic responses are characterized by the well-known descriptor “flight or fight,” while the parasympathetic responses are meant to conserve energy and maintain balance. Usually, the operation of one system causes decreased activity in the other. These branches evolved to provide us with tools to assess and respond quickly to the environment and to return to a state of balance when appropriate.

Certain spiritual experiences can be explained by the activity of these two systems and their interaction. The extraordinary relaxation of sleep corresponds to certain descriptions of meditative states. Slow repetitive rituals as found in chanting or group prayer can create this sense of tranquility and detachment (the parasympathetic system).

On the other hand, any rapid, continuous movement can lead to the experience of “flow,” a state characterized by intense focus and sense of energy (the sympathetic system).

When these two systems operate at the same time, the spillover effects create both a trancelike state and a rush of energy, measurable by hormonal effects, heart rate, breathing and blood pressure changes.

The Emotional Brain

The limbic system or emotional brain governs the generation and control of human emotions. It is the ground on which the “emotional value operator” stands. Many religious experiences encompass emotions of love, awe, joy, and ecstasy.

But that isn’t all. Electrical stimulation of the amygdala and hippocampus, for example, can produce dreamlike states and out of body sensations.

Are spiritual experiences merely a product of brain dysfunctions?

Many other researchers have explored the nature of spiritual experiences wondering if they were not simply the product of brain dysfunctions.

By comparing them to descriptions of those suffering from epileptic seizures and psychotic experiences, many similarities emerged. For example, religious hallucinations experienced by those suffering from schizophrenia can include hearing voices, visions, and sensing a disconnection to the everyday world, experiences also described by mystics throughout history.

But making comparisons also requires that we note differences. These are a few examples cited by Newberg.

For psychotics, their experiences are distressing—”God” is often an angry presence. For mystics, their experiences are most often joyful and accompanied by feelings of serenity, wholeness, and love.

Epileptic seizures also have been known to generate feelings and experiences of “wholeness” and delight, but the content is repetitive: mystical experiences can vary in both content and emotional valence. Seizures are regular, repetitive neurological events, unlike those of a mystic who may experience only a handful of such experiences in a lifetime.

The content of the experiences, generated by psychosis or seizures, is often one-dimensional—a single sense is involved—while the experiences described by mystics are a rich interplay of sense perceptions and emotions. Once a psychotic episode ends, the individual sees the “fragmented and dreamlike nature” of the hallucination. Not so for the mystic. It is an unforgettable experience, and its reality is not doubted even after years have passed.

How does the human brain know what is real?

The human mind evolved to provide the means to determine what is real. The existential operator (see table above) determines the reality of our sense perceptions aided by the sensory association areas. For example, even if a dream may seem real while we are asleep, that sense fades when we wake up.

As discussed earlier, all perceptions exist in the mind and are created by neurochemical exchanges among neurons, neural circuits, and association areas, whether eating a slice of apple pie or experiencing a sense of “Other” in a meditative state. In spite of the “mental” nature of our perceptions, our everyday experience of successfully operating in the outside world is evidence that our perceptions capture objectively “real” aspects of that world. Modern technology provides more than ample evidence for our ability to successfully manipulate and harness elemental forces and materials in the world around us.

Are spiritual experiences “real”?

There’s little doubt that the transcendent states from which religions rise are neurologically real—brain science predicts their occurrence, and our imaging studies, as well as others, have actually captured them on film.

The deeper questions: Are these unitary experiences merely the result of neurological function—which would reduce mystical experience to a flurry of neural blips and flashes—or are they genuine experiences which the brain is able to perceive? Could it be that the brain has evolved the ability to transcend material existence, and experience a higher plane of being that actually exists? (p.140)

The hypothesis on which the book is based stresses the neurological basis for the mystical experience of a “primary reality that runs deeper than material existence—a state of pure being that encompasses the lesser realities of the external world and the subjective self.” (Newberg, p. 145)

After examining evidence from multiple studies on religious experiences and from their own SPECT studies, the conclusion? Mystics are neither delusional nor psychotic. In spite of their unusual content, mystical experiences correspond to a properly functioning neural architecture and reveal what appears to the person to be a higher reality.

The nature and existence of an Ultimate reality that encompasses both objective and subjective realities cannot be determined by science. At best, current scientific techniques like those described by Newberg, have revealed a possible neurological mechanism for self-transcendence.

Newberg takes time to note also that the greatest scientific minds of the last century describe similar insights experienced by mystics. (pp. 153-54.) Their experiences, however, occurred while trying to understand the most fundamental forces at work in the material universe.

Albert Einstein, whose theories of special and general relativity turned our understanding of space and time on its head, describes a “cosmic religious feeling”:

The individual feels the nothingness of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in Nature and in the world of thought. He looks upon individual existence as a sort of prison and wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole.

For Erwin Schrodinger, all conscious beings “are all in all” and one with “Mother Earth.”

Erwin Chargaff whose research formed the foundation for Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double helix of DNA, claims that all scientists are driven by an intuition that something mysterious inhabits the material world:

If a scientist has not experienced, at least a few times in his life…this confrontation with an immense, invisible face whose breath moves him to tears, he is not a scientist.

The rest of the book is an ambitious attempt to integrate myth-making, the formation of rituals, and the origin of religion into the insights derived from the study of meditative states. Ultimately, Dr. Newberg argues that the human experience of absolute unitary being has a biological basis given the neural architecture we possess and is not merely a fabrication of a dysfunctional brain.

That is why God won’t go away anytime soon.

More consciousness resources from Purposeful Universe.