Perhaps best known for “Pascal’s Wager” (which is worth reading about) Blaise Pascal was also a brilliant mathematician, philosopher, theologian, and inventor.

Early Life and Education

Early Life and Education

Born in Clermont, France, in 1623, Blaise Pascal was largely educated at home by a tutor due to his poor health. His father-a judge and tax collector but also a man of scientific interests-had recognized his son’s brilliance at an early age. (At the age of 12 Blaise had written a treatise on the communication of sounds.) He moved the family from Clermont to Paris to increase his son’s opportunities to study with the greatest minds of that time. At 14, Blaise began attending the weekly meetings of Roberval, Mersenne, and Mydorge, meetings which eventually led to the founding of the French Academy of Sciences. By sixteen, he had written a well-regarded essay on conic sections.

Inventions

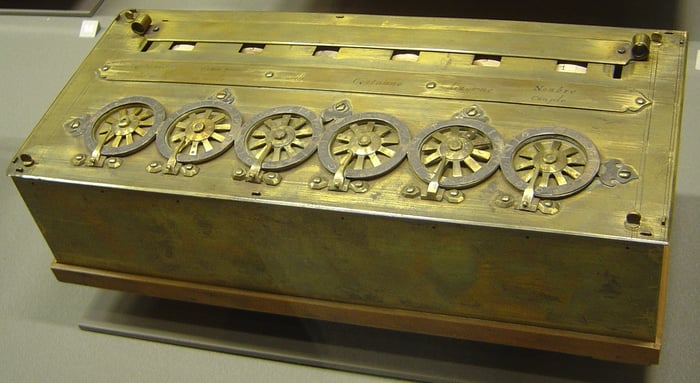

At 18, to help his father manage his accounts as a tax collector, Pascal invented a “numerical wheel calculator“ known as the Pascaline, considered by some to be the first “computer”. He is credited with a primitive version of another machine, a roulette machine. It is also reported that he was the first person to attach a watch to his wrist, popularizing the idea of a “wrist” watch.

Pascaline, an early calculator invented by Pascal. Creative Commons

Pascaline, an early calculator invented by Pascal. Creative Commons

Contributions to Math and Science

In mathematics, he is known best for Pascal’s triangle (This is fun-you should try it!) and Pascal’s theorem dealing with hexagons. With fellow mathematician Pierre de Fermat, he developed the probability theory which ultimately gave birth to statistics. He is known also for his experiments confirming the existence of a vacuum, a hotly debated topic among his contemporaries, especially since Aristotle had denied such a thing could exist. Because of his contributions to our understanding of atmospheric pressure, a unit of atmospheric pressure, the Pascal (Pa), is named after him as is a computer language, Pascal.

Evidence of the Senses: The Importance of the Scientific Method

Confirming at a young age the experiments of Torricelli and collecting evidence for his own theory of the cause of barometric variability, throughout his life Pascal insisted on the significance of measurable and verifiable data.

Additionally, according to Pascal’s thinking, agreement with facts is not the only requirement for an explanation to be true. There can be multiple possible causes for a fact which should be thoroughly investigated.

He defends the distinction of facts derived from observation as distinct from truths derived from philosophy or theology in one of his letters:

"How then do we learn what the facts are? From our eyes, Father, which are the rightful judges of facts, as reason is of natural and intelligible things, and Faith of things supernatural and revealed. But since you compel me to do so, Father, let me tell you that in the opinion of two of the greatest doctors of the Church, Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas, these three principles of knowledge, the senses, reason and Faith each have separate objects, and are certain within their range." (emphasis added)

Conversion and Contributions to Theology

At the age of 22, he began studying religion in an effort to “contemplate the greatness and the misery of man.”

According to one analysis, his most famous work, the Pensees, was meant to be a defense of Christian belief in a living God against a group of elite “gentlemen,” described as polite agnostics who were concerned more with etiquette than ethics.

Originally admiring their wit and manners before his conversion, he challenges these “sophisticated freethinkers” to recognize what even Montaigne had observed in his Essais: that man’s worst sin was arrogance originating in an exaggerated confidence in the power of human reason. Pascal rightly points out that man desires both truth and happiness but appears incapable of achieving either. His conclusion? The Christian view of man’s nature must have some merit.

In fact, for Pascal a truly rational man was one who recognized realities beyond human reason. The Christian view and the secular view were equally comprehensible, or incomprehensible, in his eyes.

"For instance, it is equally incomprehensible that God should exist or that he should not; that the soul should be joined to the body or that we should have no soul; that the world should be created or that it should not; that original sin should exist or that it should not."* (emphasis added)

The Memorial

A tattered piece of paper was found stitched into his coat after his death. On it was penned a poem or prayerful reflection about an event which occurred on a Monday in November, 1654. Pascal even specifies the time it occurred so significant was it to his life. The commentary by Romano Guardini is worth reading in its entirety, but essential quotes are highlighted below.

Certitude Given by the Holy Spirit

Something colossal has happened here. Pascal has stood in fire. We may not take the word allegorically… It is an experience of the spirit; more exactly, of the Holy Spirit, of the "Pneuma." There takes place therein an elucidation in certitude, a seizure by glory, a clarification of life, which place man on a new level of existence.

The Power of an Encounter with the Living God

Pascal, who demands for all knowledge experience—that confirmation which is only possible when one stands before the reality itself—, who has grasped the reality of nature in experiment and calculation, and the reality of man in observation and analysis—this same Pascal now stands before the reality of the living God. He will now be able to speak, also in the religious realm, with that authenticity deriving from the object itself, which he had as a physicist and psychologist. (emphasis added)

As Guardini points out, when Pascal experienced “the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” and the “Abba” spoken of by Jesus of Nazareth, he continued to be a first class mathematician, physicist, engineer, psychologist, and philosopher.

Far from impeding the progress of human knowledge, experience of and belief in God gives Pascal and potentially all scientists a heightened power to penetrate the mysteries within human vision and to contemplate the infinity of Mystery which lies beyond it.

Pascal’s witness to this truth is perhaps his greatest contribution.