The sky is full of birds, the purple lupins stand up so regally and peacefully, two little old women have sat down on the box for a chat, the sun is shining on my face—and right before our eyes, mass murder. The whole thing is simply beyond comprehension.

—Etty Hillesum, describing a scene at the Westerbork transit camp

The Holocaust produced many saints and martyrs who resisted the evil around them to a heroic degree. It is overwhelming, however, to imagine the anger, fear, and frustration of having your freedoms slowly taken away, to be forced to wear an external identifying badge, and to experience harassment and abuse simply because of your religion or ethnic heritage.

Yet this is precisely the experience of the Jewish people in Nazi-occupied Europe of the 1940s. The laws became more restrictive until the deportations began in earnest in 1941.

Amsterdam, Holland

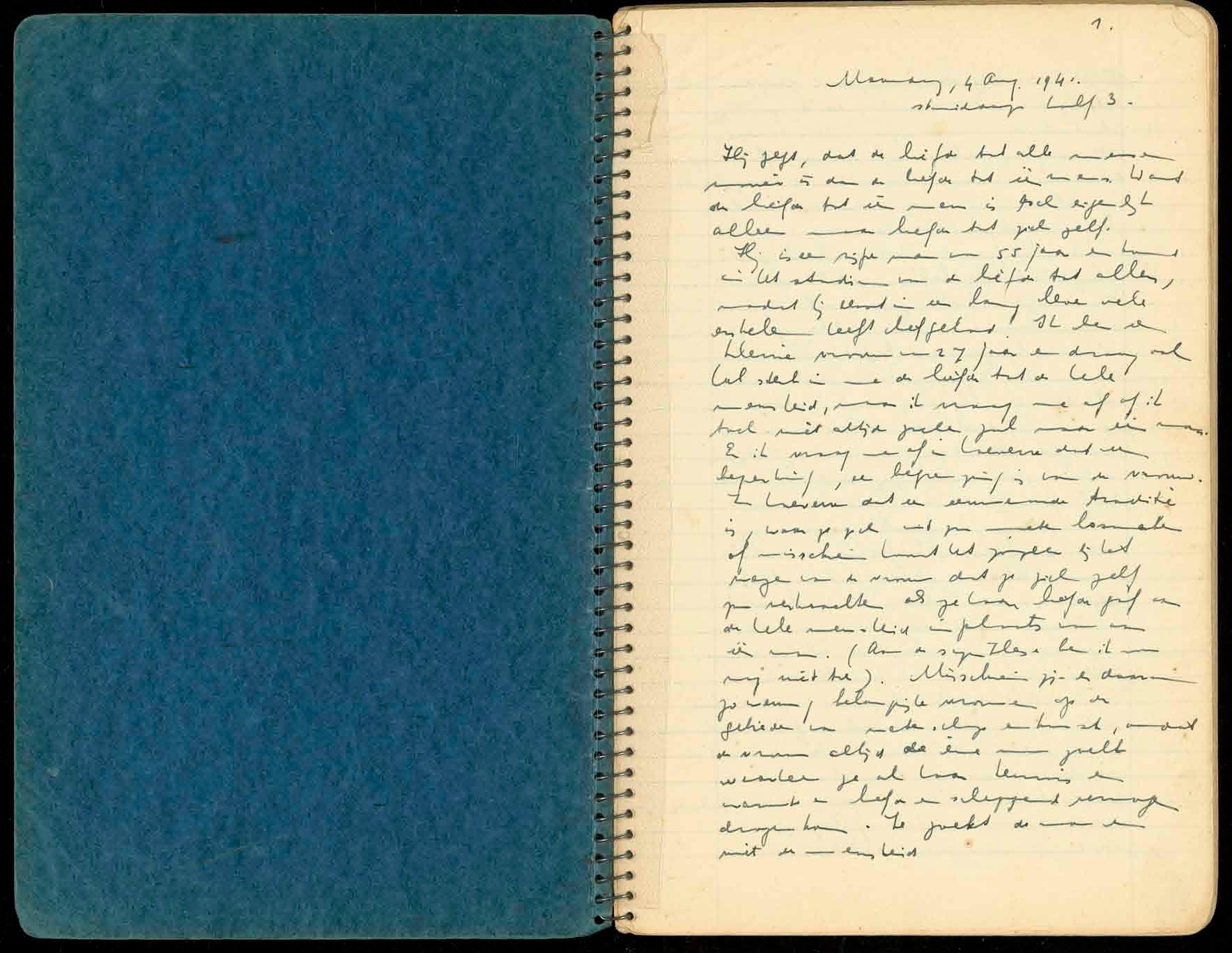

Many people are familiar with Anne Frank’s diary, but few have heard of Etty Hillesum’s diary, “An Interrupted Life.”

Etty Hillesum's diary, Part 1 of 11.

Etty Hillesum's diary, Part 1 of 11.

“An Interrupted Life” is a 27-year-old woman’s attempt to capture the events of that time—to bear witness to the evil that oozed under the floorboards and into the lives of Dutch Jews, particularly those in Amsterdam and the Westerbork transit camp. In her diary, Etty Hillesum also bears witness to the truth she fought for and found:

“I am with the hungry, with the ill treated and the dying, every day, but I am also with the jasmine and with that piece of sky beyond my window; there is room for everything in a single life. For belief in God and for a miserable end.” —Etty Hillesum

Her declaration of “belief in God” is a startling comment from this young woman. Etty’s diary begins in March of 1941 and chronicles her search for God in the midst of her internal struggles and confusion and in the external events that would eventually lead to her death at Auschwitz in November 1943.

Who was Etty Hillesum?

We know a little about her childhood and upbringing.

Her father was a classics teacher, and she had two brothers. Her brother, Mischa, who played the piano publicly for the first time at the age of six, was considered the best pianist in Holland. Before finishing his medical degree, her other brother, Japp, identified several new vitamins.

Etty too was intellectually gifted. She took her first university degree in law, followed by Slavonic languages, and finally psychology. Through her psychology classes, she was introduced to a man, 27 years her senior, who would become her mentor, lover, and spiritual partner. Referred to as “S” throughout the diary, she wrestled with him, literally, emotionally, and psychologically. His name was Julius Spier, a Jewish emigrant from Berlin, who studied under Carl Jung. Jung encouraged Spier’s talent at “psychochirology,” the reading of hands and palms, and so he had opened a psychiatric practice in Amsterdam.

His therapeutic method—characterized as “erotic tousles”—certainly raises ethical issues by today’s standards. It also caused a tremendous amount of confusion and pain for his young assistant.

What was Amsterdam like in her time?

Spier’s methods might not have raised eyebrows in Etty’s circle, however. In the forward of the 1996 edition of “An Interrupted Life,” Eva Hoffman writes:

"The interwar decades were a period of eclectic psychoanalytic experiments, of eccentric adventures in self-exploration."

Adding more color to her story is that Etty also had a relationship with the 60-year-old owner of the house she lived in with several other young people. In her diary, she questions the traditional “one man, one woman” ideal. In fact, as she and “S” became closer, she was troubled by her desire for their relationship to be exclusive. This questioning of traditional relationships is one of the reasons that feminists tend to idolize Etty. There is, however, much more to the story.

What makes Etty’s story of resistance unique?

What is most fascinating about Etty’s story is that she herself was in turmoil and “darkness” as the evil grip of the Nazi program strangled the freedom of the Jews in Holland.

Etty Hillesum, 1939 / Public Domain

Etty Hillesum, 1939 / Public Domain

It seems Etty was raised without any religious instruction. She candidly assessed her own childhood:

“[Our parents] gave us children too much freedom of action, and offered us nothing to cling to. That was because they never established a foothold for themselves. And the reason why they did so little to guide our steps was that they themselves had lost the way.”

She writes frankly about her emotional, physical, and spiritual struggles. Belief in God was a central struggle. Towards the end of her diary she wrote:

“What a strange story it really is, my story: the girl who could not kneel. Or its variation: the girl who learned to pray.”

Early on, however, she says with keen insight:

“There is a really deep well inside me. And in it dwells God. Sometimes I am there, too. But more often stones and grit block the well, and God is buried beneath. Then He must be dug out again.”

In her ongoing struggle of discovery, she surrenders to God with this prayer:

“I delight in warmth and security, but I shall not rebel if I have to suffer cold, should You so decree. I shall follow wherever Your hand leads me and shall try not to be afraid. I shall try to spread some of my warmth, of my genuine love for others, wherever I go.” —Etty Hillesum

Etty’s response to the 'piece of history that is ours'

Aided by one or two passionate debates among two of her mentors and her study of the Bible, the result of her struggle to find God led Etty to a realization of her own brokenness. In response to a friend’s question, “What is it in human beings that makes them want to destroy others?" she responded with newfound insight:

"The rottenness of others is in us, too… I really see no other solution than to turn inward and to root out all the rottenness there. I no longer believe that we can change anything in the world until we have first changed ourselves. And that seems to me the only lesson to be learned from this war. That we must look into ourselves and nowhere else." —Etty Hillesum

Etty’s reflections on suffering emerged as restrictions for the Jews increased and as the likelihood of being deported to a concentration camp became greater. Yet, her faith in God grew, as she said, “so quickly… and is now inseparable from me.”

“Give your sorrow all the space and shelter in yourself that is its due, for if everyone bears his grief honestly and courageously, the sorrow that now fills the world will abate. But if you do not clear a decent shelter for your sorrow, and instead reserve most of the space inside you for hatred and thoughts of revenge—from which new sorrows will be born for others—then sorrow will never cease in this world and will multiply. And if you have given sorrow the space its gentle origins demand, then you may truly say: life is beautiful and so rich. So beautiful and so rich that it makes you want to believe in God.” —Etty Hillesum

At first, Etty can barely say out loud to her friends, “I believe in God,” but eventually she sees her duty to share this faith and love of God with others:

“All the strength and love and faith in God that one possesses, and which have grown so miraculously in me of late, must be there for everyone who chances to cross one's path and who needs it.

“...all that really matters: that we safeguard that little piece of You, God, in ourselves. And perhaps in others as well… and defend Your dwelling place inside us to the last.”

Prayers answered

It seems that God powerfully answered Etty’s heartfelt prayers.

“Something has crystallized. I have looked our destruction, our miserable end, which has already begun in so many small ways in our daily life, straight in the eye and accepted it into my life, and my love of life has not been diminished.”

To her surprise, Etty was given a job in the Cultural Affairs Department of the Jewish Council on July 15, 1942, This council was a tool used by the Nazis to keep Jewish resistance at a minimum, but it was not viewed as such initially.

As Etty watched her fellow Jews be summoned and issued “passes” to go to Westerbork—the transit camp from which deportations to Auschwitz originated—she felt the desire to accompany them, believing that by doing so she could offer more direct help.

Etty did voluntarily go to Westerbork sometime at the end of July, 1942. At the end of August, a deathly ill Etty returned to Amsterdam where she remained bedridden for many weeks. Her lover and mentor, Spier died somewhat unexpectedly Sept. 15, the very day the Gestapo went to round him up.

Etty’s reflections continued in spite of her illness and the loss of the most significant person in her life. She strove to transform any feelings of anger or retribution into universal compassion for suffering humanity.

“I love people so terribly, because in every human being I love something of You. And I seek You everywhere in them and often do find something of You.

“I shall wait patiently until the words have grown inside me, the words that proclaim how good and beautiful it is to live in Your world, oh God, despite everything we human beings do to one another.

“It still all comes down to the same thing: life is beautiful. And I believe in God. And I want to be there right in the thick of what people call 'horror' and still be able to say: life is beautiful.” -Etty Hillesum

‘Let me be the thinking heart of these barracks.’

Etty and her family were eventually sent permanently to Westerbork camp. Etty was asked to write a description of life at the camp by a doctor whose sisters wanted to know what it was like there. He himself felt inadequate to describe it. The following are examples of what the Jews there witnessed and endured.

“To simply record the bare facts of families torn apart, of possessions plundered and liberties forfeited, would soon become monotonous. Nor is it possible to pen picturesque accounts of barbed wire and vegetable swill to show outsiders what it's like.”

Etty does describe the endless mud, the crowding, and the barbed wire that ran not only around the camp but through it. She describes the three-tiered bunks in the drafty barracks, the lice, and the lack of food and water.

In only a few months, at the end of October of 1942, Westerbork's population soared from 1,000 to 10,000. Previously, people would arrive with clothing and supplies. Towards the end, many arrived with only the clothes on their backs or in their pajamas, so suddenly had they been swept up by the Nazis.

Increasingly, older and more infirm Jews were brought in for transport. It became painfully clear that they were not destined for a “work camp.” Etty describes the fear and confusion and hopelessness.

She also mentions the tortured bodies of the young men arriving from Ellecom, where the Dutch SS were trained how to treat the Jews. She describes how many people at the camp were bitter and full of hatred. Although she herself resisted these feelings, she understood them:

“And the absence of hatred in no way implies the absence of moral indignation. I know that those who hate have good reason to do so. But why should we always have to choose the cheapest and easiest way? It has been brought home forcibly to me here how every atom of hatred added to the world makes it an even more inhospitable place. And I also believe, childishly perhaps but stubbornly, that the earth will become more habitable again only through the love that the Jew Paul described to the citizens of Corinth in the thirteenth chapter of his first letter.” —Etty Hillesum

The last words in the diary she had left behind with a friend were: "We should be willing to act as a balm for all wounds." And on a postcard thrown from the deportation train, found and mailed by a farmer, she wrote: “We left the camp singing.”

A friend at the camp described her departure on that train to Auschwitz in September 1943. In a letter to Etty’s friends back in Amsterdam, he described her as she stepped onto the platform of the deportation train:

“Talking gaily, smiling, a kind word for everyone she met on the way, full of sparkling humor, perhaps just a touch of sadness, but every inch the Etty you all know so well.”

And:

“After her departure I spoke to a little Russian woman and various other proteges of hers. And the way they felt about her leaving speaks volumes for the love and devotion she had given to them all.”

The end of her journey

Etty Hillesum died at Auschwitz on Nov. 30, 1943, but the real conclusion to Etty’s story is found in a dialogue she relates with her friend, Klass, an ardent Communist:

“I see no alternative, each of us must turn inward and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others.

And you, Klaas, dogged old class fighter that you have always been, dismayed and astonished at the same time, say, ‘But that—that is nothing but Christianity!’

And I, amused by your confusion, retort quite coolly, ‘Yes, Christianity, and why ever not?’”

Read Also:

"Never Forget": a short story that documents the tragic yet miraculous childhood of a Jewish boy during the Holocaust—and why we must never forget what happened during the Holocaust.

More articles like this:

The Amazing Story of Maximilian Kolbe (and Why it Matters Now More Than Ever)

4 Heroic Resisters to Naziism