Poetry is a powerful force of the written word. It has the ability to lead, nurture, and guide us in our lives. It provides a connection across the human experience and inspires the world.

Poems have the capacity to form a bridge between that which we do not understand and the truth. If read thoughtfully, it can aid us in being better people to those around us and helps us understand the meaning of life.

Beautifully, poems are also a great example of the written word that can discuss the deep, dark, and tragic but still leave us with an overwhelming sense of hope, love, and compassion.

Below are five Catholic poets whose life’s journey is as inspiring as their words.

Catholic Poet and Saint: Teresa of Avila

Born on March 28, 1515, Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada was the daughter of Alonso Sánchez de Cepeda and Beatriz de Ahumada y Cuevas. Her father, Alonso, was a wool merchant and also one of the most wealthy men in Ávila. Brought up as a dedicated Catholic.

After completing her education, Teresa went to live with her uncle and decided to pursue a religious vocation. However, shortly after becoming a nun, Teresa contracted Malaria, which left her incredibly sick for an extended period of time. When she recovered, she began exclaiming the spiritual nature of healing.

Due to the lack of reception to the stories of her healing journey, she began to shy away from prayer. It would not be until she was 41 that she would return to a life of prayer.

Portrait of Teresa of Ávila by François Gérard / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At 43, St. Teresa decided to recommit to a life of simplicity. She then felt called to leave her convent (which she believed prevented her from a true life of prayer) and established her first convent. She then traveled around Spain and set up many more convents, becoming a true leader.

In 1580 she completed what is believed to be her most influential body of work: Castillo Interior/ Las Moradas (Interior Castle/ The Mansions). But her written words have lived on to reach around the globe and across the changing times.

St. Teresa Avila’s “Nada Te Turbe”

Let nothing disturb you,

Let nothing frighten you,

All things pass away:

God never changes.

Patience obtains all things.

He who has God

Finds he lacks nothing;

God alone suffices.

St. Teresa Avila’s “Nada Te Turbe” (translated to English from the original language of Spanish) is a beautiful reminder of the importance of practicing patience through God. It also encourages us to surrender to Him completely. As a result of heeding these gentle reminders, we are able to find value and meaning outside of ourselves and our lives—in Christ.

Catholic Poet Patrick Kavanagh

Patrick Kavanagh was born in Inniskeen, County Monaghan, Ireland. He was one of ten children born to James Kavanagh and Bridger Quinn. His father was a farmer and cobbler and raised his family on a small, struggling farm. In fact, despite all the hardships that accompanied his family and lifetime, his homeplace often inspired the naturistic aspect of his poetry.

Kavanagh’s education was cut short when he left at the age of 13. He then went to apprentice under his father as a cobbler and helped on the family farm. Eventually, after publishing his first verse in 1929 and his second in 1930, Kavanagh walked 80 miles to see his older brother, Russell, in Dublin. Russell, a teacher, aided Kavanugh’s education and supported his goal of committing to a literary career. In 1936, he released his first collection, Ploughman and Other Poems, in 1936.

Poet Patrick Kavanagh by the National Library of Ireland on The Commons / No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

With the outbreak of World War II—along with many other Irish writers—Kavanagh lost access to his publishers and could not continue releasing his prose. After the war, Kavanagh worked many journalist jobs (e.g., a gossip columnist in the Irish Press, a writer for The Standard, and a monthly “diary” writer for Envoy). He even had his semi-autobiographical novel, Tarry Flynn, turned into a play performed at Abbey Theatre.

However, despite his acclaim and accomplishments, Kavanagh never found comfort with his finances nor an easier life. He passed away after contracting an illness at the first performance of Tarry Flynn. Yet, to this day, his poetry lives on and influences the faithful and writers alike.

Patrick Kavanagh’s “Canal Bank Walk”

Leafy with-love banks and the green waters of the canal

Pouring redemption for me, that I do

The will of God, wallow in the habitual, the banal,

Grow with nature again as before I grew.

The bright stick trapped, the breeze adding a third

Party to the couple kissing on an old seat,

And a bird gathering materials for the nest for the Word

Eloquently new and abandoned to its delirious beat.

O unworn world enrapture me, encapture me in a web

Of fabulous grass and eternal voices by a beech,

Feed the gaping need of my senses, give me ad lib

To pray unselfconsciously with overflowing speech

For this soul needs to be honoured with a new dress woven

From green and blue things and arguments that cannot be proven.

“Canal Bank Walk” is the religious sonnet that Kavanagh wrote after leaving the hospital after he underwent surgery for his lung cancer. While in the hospital, he claimed to have undergone a spiritual experience. “Canal Bank Walk” was inspired by letting go of the answer-seeking and intellectual side of a relationship with God and fully coming to Him. The sonnet delightfully compels us to have eyes for ordinary things in life that are a direct reflection of God.

Catholic Poet Richard Crashaw

Poet Richard Crashaw had a very interesting life that led him to Catholicism.

He was born in London, England, and was the only son of the Anglican divine William Crashaw. His father was known for publishing numerous pamphlets advocating Puritan theology and was incredibly critical of Catholicism. However, despite his disagreement with the Catholic faith, he admired the devotion of Catholics. William was also known to have one of his most extensive theological libraries. This library consisted of many Catholic works and was young Richard Crashaw’s beginning of deep theological thought.

Orphaned at just 13, Richard Crashaw became under the guardianship of Sir Henry Yelverton and Sir Ranulph Crewe and journeyed on to great educational accomplishments.

Portrait of Richard Crashaw by Unknown artist / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Crashaw went on to become a Fellow of Peterhouse at Cambridge and, in 1638, was ordained into the priesthood of the Church of England. He ended up preaching at St. Mary the Less, where he became passionate about the Catholic tradition. Crashaw would hold late-night prayer vigils and display images of the Blessed Mother Mary and crucifixes. His leadership of the church drew Puritan spies who believed he was preaching “popish” idolatry.

With the coming of the English Revolution in 1643, Crashaw was excommunicated. With his excommunication, he settled in the Netherlands. During this time, he is believed to have converted to Catholicism. Eventually, he pilgrimaged to Rome, Italy, was granted a post with Cardinal Giovanni Battista Maria Pallotta, and resided at English College.

Crashaw began to notice immoral behavior from those around Pollotta, which caused him to come forward. In doing so, he created many enemies and had to leave the college. He went on to Loreto, Marche, where he would inevitably die of a fever in 1649. His death raised suspicions that he was poisoned by the enemies he created in Pallotta’s entourage.

Richard Crashaw’s “The Recommendation”

These houres, and that which hovers o’re my End,

Into thy hands, and hart, lord, I commend.

Take Both to Thine Account, that I and mine

In that Hour, and in these, may be all thine.

That as I dedicate my devoutest Breath

To make a kind of Life for my lord’s Death,

So from his living, and life-giving Death,

My dying Life may draw a new, and never fleeting Breath.

“The Recommendation” by Richard Crashaw is a beautiful imagining of giving our entire selves to Him. It calls us to trust in Our Father and allow our life here on earth and beyond to be safe in His loving hands.

Catholic Poet Dame Edith Sitwell

Edith Sitwell was born in Yorkshire in 1887 and was the oldest of three. Often citing that her home life was filled with unloving parents, she frequently described her childhood as sad and admitted to having spent most of it with her governess—even moving in with her governess when she was 26 years old.

Portrait of Edith Sitwell by Roger Fry / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

While living in London, she worked for the Daily Mirror (where she also published her first poem) and hosted many meetings for poets in her flat. Sitwell was made a dame in 1954.

After she had begun to fall ill due to her condition, Marfan syndrome, Sitwell converted to Roman Catholicism and asked fellow author Evelyn Waughn to be her godfather. She passed at 77 with her final work, The Outcasts, the beautiful conclusion to a lengthy and meaningful poetry career.

Dame Edith Sitwell’s “Still Falls the Rain”

Still falls the Rain—

Dark as the world of man, black as our loss—

Blind as the nineteen hundred and forty nails

Upon the Cross.

Still falls the Rain

With a sound like the pulse of the heart that is changed to the hammer-beat

In the Potter’s Field, and the sound of the impious feet

On the Tomb:

Still falls the Rain

In the Field of Blood where the small hopes breed and the human brain

Nurtures its greed, that worm with the brow of Cain.

Still falls the Rain

At the feet of the Starved Man hung upon the Cross.

Christ that each day, each night, nails there, have mercy on us—

On Dives and on Lazarus:

Under the Rain the sore and the gold are as one.

Still falls the Rain—

Still falls the Blood from the Starved Man’s wounded Side:

He bears in His Heart all wounds,—those of the light that died,

The last faint spark

In the self-murdered heart, the wounds of the sad uncomprehending dark,

The wounds of the baited bear—

The blind and weeping bear whom the keepers beat

On his helpless flesh… the tears of the hunted hare.

Still falls the Rain—

Then— O Ile leape up to my God: who pulles me doune—

See, see where Christ’s blood streames in the firmament:

It flows from the Brow we nailed upon the tree

Deep to the dying, to the thirsting heart

That holds the fires of the world,—dark-smirched with pain

As Caesar’s laurel crown.

Then sounds the voice of One who like the heart of man

Was once a child who among beasts has lain—

“Still do I love, still shed my innocent light, my Blood, for thee.”

Dame Edith Sitwell’s “Still Falls the Rain” is her most well-known poem and is a stellar comparison of The Blitz and The Crucifixion. Utilizing dark imagery and biblical references, Sitwell captures a bleak feeling but ends the poem with a sense of hope—a hope that Christ will be the light through our dark times and suffering. As a result, calling us to experience our pains and strife with the assurance that we are taken care of and are presented with the opportunity to turn to Him.

Catholic Poet Joyce Kilmer

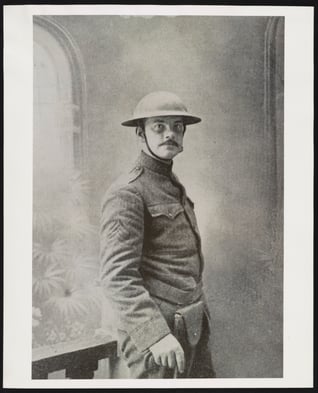

American writer and poet, Joyce Kilmer, is often recognized as one of the “would be” greatest American poets; his life was cut short by a sniper’s bullet at the Second Battle of the Marne at only 31 years of age.

During his tragically short life, he led an incredibly fulfilled life. In his professional career, Kilmer started by working for Funk and Wagnalls. His job was to define words for five cents a word to craft the 1912 edition of the Standard Dictionary; however, he was such a workhorse that the publishing house had to put him on a regular salary instead!

Kilmer then published his first book of verse (Summer of Love) in 1911 and, in 1912, became a special writer for the New York Times Review of Books and the New York Times Sunday Magazine. Also fulfilling his professional career were many lectures, to which he rarely prepared prior—his history of defining words and research afforded him so much knowledge that he could utilize at any given moment.

Poet Joyce Kilmer in uniform during his service in the 165th Infantry Regiment, PPOC, Library of Congress / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

More impressively, though, Joyce Kilmer’s faith was at the core of his life. He married Aline Murray (also a prolific writer) and had five kids together. When their daughter, Rose Kilmer, was diagnosed with poliomyelitis (i.e., infantile paralysis), Joyce turned to faith. After many exchanges with Fr. James J. Daly, the Kilmers converted to Catholicism in 1913. While Kilmer always believed and had a belief in The Church, he says in a letter to Fr. Daly:

“Faith did come, it came, I think, by way of my little paralyzed daughter. Her lifeless hands led me; I think her tiny feet know beautiful paths. You understand this, and it gives me a selfish pleasure to write it down.”

—Poems, Essays and Letters - 2 Volumes

Kilmer’s journey of faith reminds us that suffering offers us many opportunities to draw closer to Him.

Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees”

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

Kilmer’s poem “Trees” inspires us to comprehend that all the art in the world can never compare to the beauty and complexity of God’s creations. It truly celebrates God’s creation and work done at His hands.