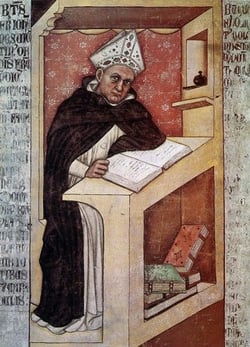

St. Albert Magnus was a great saint who used his gifts and talents in the service of God.

For centuries Saints, such as St. John Bosco, St. Teresa of Calcutta, St. Pio of Pietrelcina, St. Ambrose of Milan, St. Benedict of Norcia, St. Dominic, St. Thomas Aquinas and others, contributed immensely to the development of Catholic schools, hospitals and Christian culture. Some of these Saints earned widespread recognition and fame while others have been largely ignored or forgotten. St. Albert Magnus is one of those Saints whose legacy is still at work today within the Catholic Church but whose contributions are largely forgotten.

St. Albert and Academia

St. Albert was born in Bavaria, Germany at the start of the 13th century and studied at the University of Padua where he received extensive academic formation in Aristotle. His devotion to his formation and faith led him to the priesthood where he was ordained as a Dominican Friar shortly after completing his studies.

Over the next few years, St. Albert studied and lectured at numerous academic institutions,monastic communities and seminaries across Italy, France and Germany, where he attained mastery of a broad range of academic disciplines such as biblical theology, metaphysics, logic, botany, astronomy, physics, mathematics and anatomy.

Over the next few years, St. Albert studied and lectured at numerous academic institutions,monastic communities and seminaries across Italy, France and Germany, where he attained mastery of a broad range of academic disciplines such as biblical theology, metaphysics, logic, botany, astronomy, physics, mathematics and anatomy.

The extent of St. Albert’s knowledge and reputation as a great lecturer merited him the position as Head of the Department of Theology at the University of Paris, the most prominent academic institution in the western world at the time where he rose to fame and prominence during the course of his career. As a distinguished professor of theology, St. Albert published the Summa de bono, one of the finest commentaries on theology and metaphysics and was involved in the formation and instruction of St. Thomas Aquinas, one of his many students.

As a leading academic figure of the Catholic Church and academia, St. Albert helped develop the curriculum and formation programs for postulates entering into the Dominican Order. He mandated the instruction and mastery of Aristotle as one of the key pillars of formation for Dominican Friars. This requirement is still the basis of formation for most religious orders and seminaries today.

In 1265, St. Albert along with Pierre de Tarentaise, Bonushomo Britto, Florentius and his student St. Thomas Aquinas developed a program of studies for postulates in Rome (now the Angelicum) for formation. Today, the Angelicum is considered one of the finest institutions for instruction, scholarship, and formation for religious and clergy within the Catholic Church with many great saints, scholars, and writers having passed through their doors across the centuries.

Towards the end of his academic career, numerous bishops and his superiors requested St. Albert to become Bishop of Regensburg, Germany which he humbly accepted. As bishop, St. Albert chose to walk across his diocese on foot rather than horseback as an act of solidarity with his people. In his book, On Union with God, St. Albert, said that one must “Spare no pains, no labour, to purify thy heart and to establish it in unbroken peace.” As part of his pastoral ministry to his diocese, St. Albert helped further peace and better relationships between the Church, government and civil society, earning the admiration of all.

Apart from his immense contributions to the world of academia, his vocation as a Catholic priest, the formation of postulates in the Dominican Order, the development of academic institutions and the publication of excellent books, St. Albert set the standard of what it meant to be a disciple of Christ and a custodian of Truth. His depth of knowledge, excellence of character and sense of magnanimity is an exemplar for all Catholics to aspire to. The institutions he developed, along with his fellow friars set a very high standard of scholarship, stewardship, and fidelity to the Catholic Church.

St. Albert and the West Today

In the history of the West, the Catholic Church has played and continues to play a pivotal role in the formation of key institutions such as schools, universities and hospitals, while championing the cause of universal access to education, the concern for the poor and the rule of law. However, within the Catholic Church and in academia today, we are facing divisions concerning the Church’s teaching on the dignity of the human person, the care for the unborn, and the sanctity of marriage. In most academic institutions in the West and abroad, the study of Aristotle, sacred scripture, the cultivation of virtue, the principles of a liberal arts education and the impetus of self-discipline are either missing or non-existent in most universities.

Many students and instructors lack an understanding of the Church’s teachings rooted in theology, revelation, and philosophy. In order to remedy our culture of this ignorance we need to go back to our roots. The sad state of affairs within our Church with the sexual abuse crisis and the loss of the Catholic identity in our Catholic institutions is the outcome of this reality. It is up to a new generation of Catholics rooted in their faith with a deep relationship with Christ, to rise up to the challenge and to defend the principles of Christian solidarity that have built and defined the West over the past two millennia.

The cultural excellences of our culture such as the production of great books, science, fine works of art, classical music and beautiful architecture owes its existence to the work of devout Catholics who had an encounter with the living God, were obedient to His will and were radically transformed by His presence. In teaching and studying the lives of great saints such as St. Albert Magnus and others, we can bring about a cultural renewal within our Church that is so desperately needed.

St. Albert Magnus is an example of an obedient servant of the Lord who used his gifts and talents in the service of the Truth. His submission to the will of God and his longing for union with Him transformed the life of his students and the history of the Church. We should seek to do the same if we are truly concerned about the state of our culture and our church.

Reference: Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture