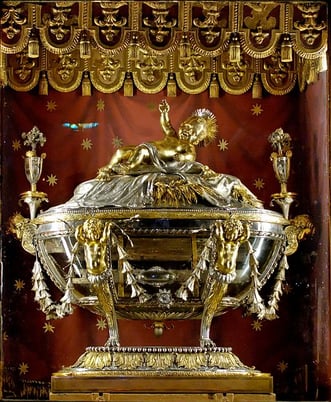

On the Esquiline Hill in Rome stands a beautiful, ancient basilica once called “St. Mary of the Crib.” Accounts dating to the 7th century record the presence of sycamore wood from the manger where the baby Jesus lay. Today, the wood is encased in a gleaming silver and gold reliquary located under the church’s high altar.

At the bottom of curved stairs, in a chamber that seems hushed despite crowds, the wood supports a golden infant whose chubby arm is eternally raised to bless. It all serves as a constant reminder that in the Christian faith, God became a little child.

Relic of the Holy Cradle, confession of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore by Jastrow / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

An Early Witness to the Nativity and the Christmas Crib

Whatever one thinks about relics like the “Christmas crib,” there is no denying that the Church of St. Mary Major (as it is now called) bears witness to a tradition of remarkable longevity. The first church on the site was built in the A.D. 300s, shortly after Christianity became legal in the Roman Empire. Less than a century later, the church was rebuilt and expanded to commemorate the famous Council of Ephesus, which affirmed the doctrine of God’s incarnation as a human baby. During this time, it is believed Pope Sixtus III may have overseen the creation of the world’s first Nativity scene, which consisted of a small, cave-like “stable” into which the faithful could place relics and offerings. By the 7th century, this “stable” included the large pieces of sycamore now visible under the church’s high altar. Later, in the 13th century, the sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio enriched the space with marble figures representing the Holy Family, the Three Wise Men, and some charming animals. These famous sculptures can still be seen today in the church’s museum.

Thus, since its conception in the A.D. 300s, when a miraculous August snowfall supposedly pinpointed its future location, the Church of St. Mary Major has never stopped proclaiming Christmas. It has survived looting, fire, and the near abandonment of Rome in the “Dark Ages.” When it was nearly 1000 years old, it was imperiled by a catastrophic earthquake, not to mention the chaos of the bubonic plague. Yet through it all, the church has never lost its splendor, and it continues to embody the Christmas message, impressing even the unbelieving and indifferent.

Cultural Traditions and Modern Philosophy

In 1935, as the Nazi threat was rising in Europe, the Marxist Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote his famous essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Still widely read, this essay examines the cognitive effects of modern mass manufacturing. How, Benjamin wondered, is modern human consciousness affected by a built environment in which there are no longer traces of the handmade, of human labor, of deep history and deliberate choice? How are our psyches impacted by immersion in standardized, carbon-copy, machine-made settings? Do such conditions affect human happiness? Is the world somehow losing its soul?

Most famously, Benjamin’s essay examined the decline of what he called “cult value” in the face of “exhibition value” in the modern West. “Exhibition value” can be understood as shallow, social signaling that has little basis in heritage or lived experience. It is a kind of manipulative performance that helps one “get ahead” or get quick results. “Cult value,” on the other hand, is the slow-cooked product of “cultivation,” or true culture—something hard-earned and incrementally developed, bearing the authority of age and enriched by the love and effort of generations. There was something almost holy about “cult value,” to Benjamin—though it was becoming rapidly forgotten in the modern world. Not a religious man himself, the Marxist Benjamin nevertheless respected the mysterious power of religious objects and spaces. Had he survived World War II, some experts suspect Benjamin may have traded his essentially atheistic Marxism for a more enchanted view of the universe.

As Walter Benjamin knew, places like St. Mary Major radiate a type of “cult value”—that is, deep cultural investment and reverence—in a way that surprises and challenges modern visitors used to a consumerist, “throwaway” world. That’s why my college students from the fairly “new” American city of Seattle (incorporated only in 1869) never fail to stand in awe of the dignity of St. Mary’s Major. The church’s age, patina, wear, and witness point to something bigger and deeper than modern minds can easily comprehend. It humbles our pride and reminds us of our ephemerality.

Experiencing the Meaning of Christmas through the Christmas Crib

From the entrance to the altar, the church of St. Mary Major lends a Christmas experience at any time of year. It is approached through a grand façade added 1300 years after the erection of the ancient building behind it—yet glimpses of medieval mosaics are still visible behind the newer stonework. When visitors leave the bustle of the street behind, passing through ornate arches, they are struck by the sudden hush of a cavernous but glittering interior. Though 1600 years old, the sanctuary of St. Mary Major is impressively huge and solemn, absorbing the small movements of hundreds of visitors in its marble floors and mosaic-covered walls. Even the least reverent and most distracted tourist feels a sudden, confusing inclination to pay respect—perhaps even to bow or kneel. Dedicated to Mary, the mother of Jesus, it is appropriate that this church offers a grand, almost maternal embrace: weighty, beautiful, welcoming, and encompassing. Equally fittingly, the enormous mosaic in the apse of the church, lavish with gold, shows a beautiful, humble Mary seated in heaven with Jesus.

And all this dignity and splendor draws the visitor forward, inward, and downward to the devotional focus of the great church: the Christmas crib. These rustic pieces of wood are not much to look at on their own, but they bear witness to something much greater and more splendid. According to longstanding tradition, they held the very body of God! Though the ancient pieces of wood housed at St. Mary Major can’t be definitively traced to that first Christmas night, they do manifest an earth-shattering idea: that the divine came to Earth in material form to share humanity’s sufferings. The incongruous placement of a golden child atop ancient, splintered boards (in the form of the above-pictured reliquary) eloquently bespeaks the paradox at the heart of the Christian religion.

Recovering Fullness by Connecting with the Past

In our twenty-first century, which has jettisoned so many longstanding traditions, Christmastime is one of the last points on the calendar when the holiness and mystery of what philosophers call “cult value” can be felt by almost everyone. Many of us have some kind of time-honored tradition or a few precious objects that make their appearance at this time of year, reminding us of a cosmic story much larger than our own. Many of us feel a yearning or thrill when we see heirloom Nativity scenes on mantles, the lights of Christmas trees glittering in the dark, or the flickering of candles reflected on windows. When we look into the cold dark of the winter night sky, admiring the brightness of the stars, we can’t help but feel connected to our ancestors thousands of years ago who sought guidance in that very same darkness.

In many ways, the thing we call “modernity” has asked us to forget the past, forget our heritage, and forget deeply rooted human patterns in pursuit of the “newer” and “better.” It has declared ancient traditions and age-old truths “obsolete”—largely in the interest of selling novel products or effecting shifts in political power. But as the modern West becomes satiated with—even wearied by—constant appeals to individualistic self-gratification and endless consumption, its heart opens again to ancient mysteries. Everywhere, both the young and the old (and especially the young!) long for connection with the deep past, together with a broader, cosmic perspective that sees profound connections among people of all generations. Even as interest in “pagan” magic is on the rise (in the form of crystals, astrology, etc.), so is interest in the forms of traditional religion.

Basilica Papale di Santa Maria Maggiore by Stella aboaf / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Basilica Papale di Santa Maria Maggiore by Stella aboaf / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

And watching it all, through grand arches like shadowed eyes, is the Church of St. Mary Major. As yearning hearts seek new ways to find meaning, to reconnect with the forgotten divine, she will never stop proclaiming the moment when the Divine became Man, under the golden light of a single star, in a rugged, humble manger.

*Featured Image Credit: Santa Maria Maggiore (Rome) by User:MatthiasKabel / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons / Cropped from original file