From the math that measured the “red shift” of Edwin Hubble, to mapping and measuring the luminosity and composition of stars, women have played crucial but often hidden roles in the science of astronomy.

There was a time when a “computer” was literally a person who did computations.

This story of the “Harvard Computers” is much like the story in the 2016 movie Hidden Figures, the story of three African American women-also known as “computers”-who played hidden roles in NASA’S race to launch the first manned space flight.

In the late 1880’s, the Harvard Observatory needed such “computers” to analyze and care for the observatory’s growing photographic glass plate collection. These plates were important, because they captured more detailed information than could be viewed in the limited field of a telescope. The “spectrograms” captured on these photographic plates gave clues about the size, the temperature, and (eventually) the composition of each star. The analysis of these plates required focused attention and diligence.

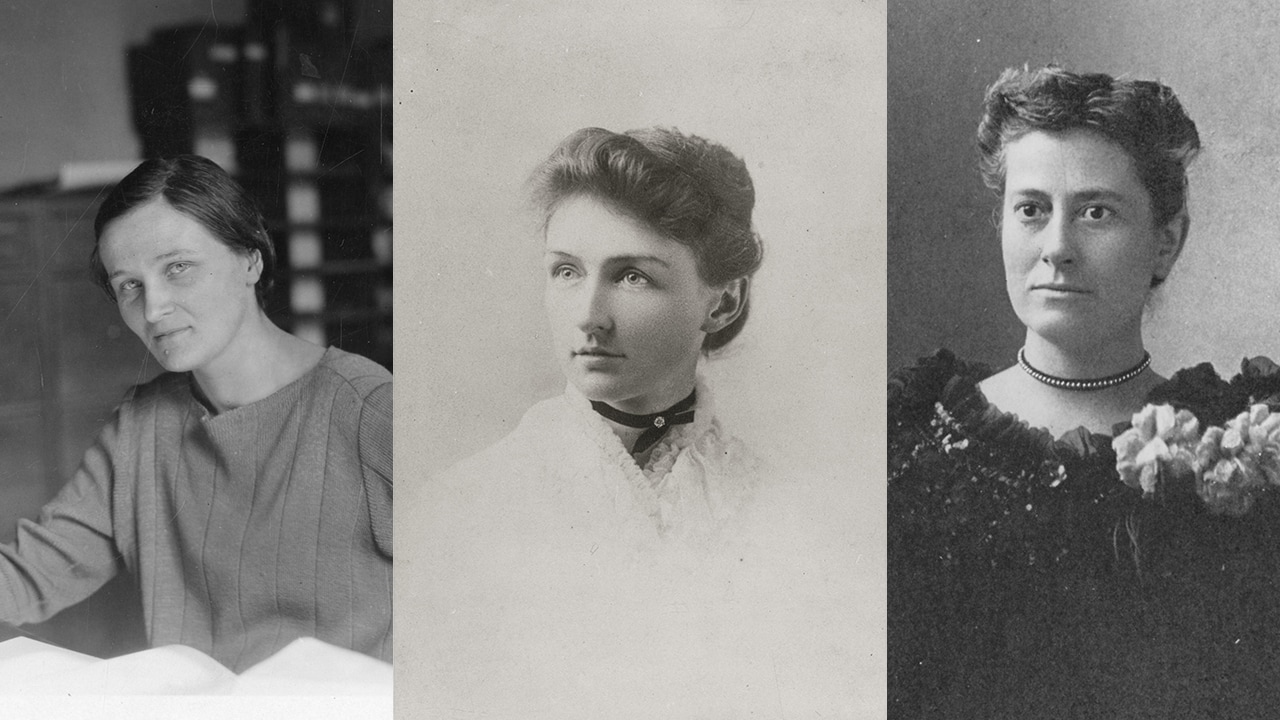

Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin, Annie Jump Cannon, and Williamina Paton Fleming. From Wikipedia.

Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin, Annie Jump Cannon, and Williamina Paton Fleming. From Wikipedia.

The First Harvard Computer

The story is told that in 1881, Pickering, the director of the observatory, became frustrated with the men working on the project and exclaimed, “My Scottish maid could do better!” He proceeded to teach her how to analyze stellar spectra using a magnifying glass.

Thus, Williamina Paton Fleming (1857-1911) became the first of the Harvard Computers. She was his maid, but Pickering, impressed by her intelligence, had already employed her at the Observatory for administrative tasks as well. During her career, even while keeping up with an increasing number of such tasks, Fleming discovered 10 novae, 52 nebulae, and 310 new variable stars. It is also fairly certain that she was the first person to see the Horsehead nebula on one of the glass plate photographs from 1888.

This group of Harvard “computers” included four other incredible women: Annie Jump Cannon, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Antonia Maury, and Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. Let’s take a peek at their work.

Many Firsts

Annie Jump Cannon (1863-1941) is best known for her work grouping stars together based on specific characteristics. This classification system is still in use today and is familiar with its mnemonic: O Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me (OBAFGKM).

She discovered 300 variable stars, five new stars, and one spectroscopic binary. Her career encompassed many firsts for women including: the first female officer of the American Astronomical Society, the first to win the Henry Draper Medal of the National Academy of Sciences (1931), the first to be elected an honorary member of the British Royal Astronomical Society, and the first woman to be awarded an honorary degree by Oxford University (1925).

Cannon was truly a stellar person in the history of astronomy!

Astronomy in Her Genes

Antonia Caetana Maury (1866-1952) was the granddaughter of John Draper, the first to successfully photograph the moon, and the niece of Henry Draper, the first person to photograph stellar spectra. After graduating from Vassar College with honors in physics, philosophy, and astronomy, Maury was hired by Pickering to study spectra of bright northern stars.

Because the more recent photographic plates contained more details than those used by Fleming and Cannon, she developed a more sophisticated classification system which resulted in Maury’s own stellar classification catalogue (based on her examination of 4,800 plates). Published in 1897, the Catalogue was the first observatory publication credited to a woman.

“[T]he most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy”

Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin (1900-1979) was the first person to obtain a PhD in Astronomy at Radcliffe College (1925), and in 1956, became the first female tenured professor and department chair at Harvard University.

Her famous 1925 thesis concluded – contrary to the understanding at that time – that hydrogen and helium were the dominant elements of the Sun and stars. This revolutionized the field of astrophysics.

The Mind Behind the Math of the Red Shift

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921) was assigned to study the variable stars found in the Small and Large Megellanic Clouds. In the course of this work, she identified 1,777 variable stars and discovered the "period–luminosity relationship" or "Leavitt's law" which allowed astronomers to measure the distance between Earth and distant galaxies. This relationship was made famous when Edwin Hubble used it to determine that the galaxies under his study were in fact moving away from the earth – the famous “red shift”.

Leavitt also developed and refined a scale of stellar brightness, accepted by the International Committee of Photographic Magnitudes in 1913.

Becoming increasingly deaf as a result of an illness she contracted in 1892, her work was interrupted often by subsequent illnesses, including the cancer that eventually led to her early death at the age of 53.

In spite of her suffering and struggles, the strength of her character was not dimmed. She was remembered by Solon I. Bailey, director of the Observatory at the time of her death, as having “the happy faculty of appreciating all that was worthy and lovable in others, and was possessed of a nature so full of sunshine that, to her, all of life became beautiful and full of meaning.”

Leavitt literally brought light to her peers.

The Genius of Women

The hidden story is that the diligent work and astute observations of these “Harvard Computers” produced some of the most significant advances in astronomy in the first half of the 20th century. Their contributions are surely included among the “great works of God” recognized by St. John Paul II in his Letter to Women (1995) and reveal the genius of the work of women in astronomy.