In 2002, John Paul II addressed the Pontifical Academy of Sciences at the beginning of its plenary session with “The Cultural Values of Science.” Eighteen years later, the truth of his words still resonates:

“By protecting its legitimate autonomy from economic and political pressures, by not giving in to the forces of consensus or to the quest for profit, by committing itself to selfless research aimed at truth and the common good, the scientific community can help the world’s peoples and serve them in ways no other structures can." -Pope John Paul II [emphasis added].

Truly exciting advances in medicine and technology are proceeding in leaps and bounds. One of the most remarkable is the capability of “gene editing” via a technique known as CRISPR. Before diving into the what, the why, and how of CRISPR, however, it might be a wholesome exercise to take a look back in time.

The year is 1973

Among the papers of a long-deceased Neurology department chairman at a large university was a 1973 pamphlet from CalTech and its affiliate, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The pamphlet expressed great hope and excitement for the application of new engineering technologies to health care. One of the technologies described is ultrasound, initially developed by the military.

National Cancer Institute / Public domain

National Cancer Institute / Public domain

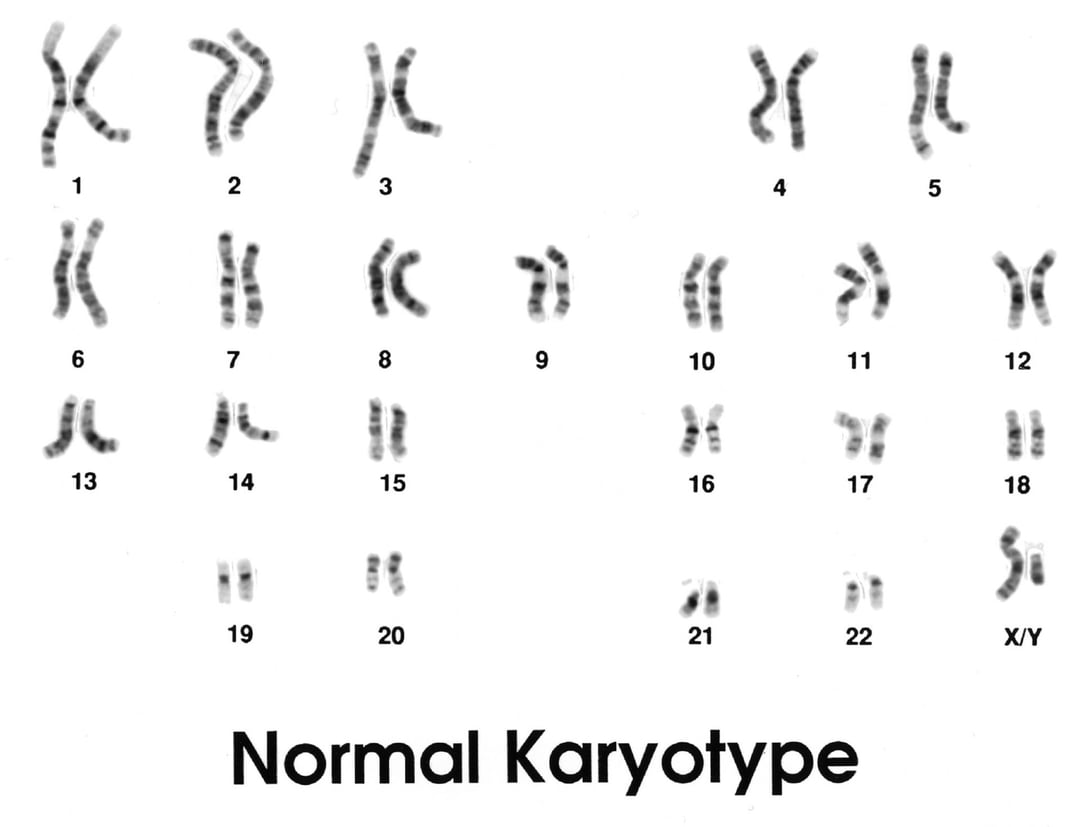

What use does the author see for this technology? He first describes advances in “karyotyping” and the identification of genetic abnormalities in utero via amniocentesis. He specifically mentions “mongolism,” known now as Down syndrome. (Jerome Lejeune discovered the extra copy of #21 chromosome in 1959, hence its other name, Trisomy 21.)

The author’s excitement is that ultrasounds can be used to safely perform amniocentesis which would allow doctors to identify the genetic “accident” of mongolism, leading to therapeutic abortion. He concludes that taxpayers would be saved huge sums of money for the maintenance and support of such an individual and that parents would be spared the drastic emotional trauma for producing a “genetic accident.”

Society has come a long way since then

Fortunately, not only has “scientific medicine” advanced, but due to indefatigable efforts of several Down syndrome families in the 1970s, our ability to care for, provide early intervention, and support these individuals and families has advanced exponentially.

Currently, there are many stories of successful, enterprising Down syndrome individuals. One young woman, Grace Strobel, after being teased by her peers, started an educational outreach called The Grace Effect to teach others what it is like to live with the disabilities associated with Down syndrome. Now she is a successful model!

The story of how Down syndrome children and adults have become accepted, even welcomed, in many (not all) cultures is a long one. Part of the story of this seismic shift in attitude is the tireless efforts of pro-life and Christian advocates, not unlike the Christianization of the West mentioned in this ebook:

“Without the conquest of Christianity… billions of people may never have embraced the idea that society should serve the marginalized or be concerned with the well-being of the needy, values that most of us in the West have simply assumed are ‘human’ values.” -Stephen Bullivant [emphasis added]

Keep this in mind as we turn our attention to the cas-9 gene editing machine.

Changing genes: CRISPR

The one chromosome difference in Down syndrome individuals highlights the significant differences resulting from an alteration of our genome. Although such changes occur usually by mutations, the gene-editing technique known as CRISPR creates such changes at will.

It is as astonishing as it is alarming.

This new technology is based on a bacterial “machine” discovered while studying how bacteria defend themselves from viruses. This research tool precisely edits genes to suppress or alter them in order to study their function or to produce desired characteristics. It is easy to imagine that this technique was one of many behind the following remark of Pope Francis in his March 27th “Urbi et Orbi” address:

“In this world, that You love more than we do, we have gone ahead at breakneck speed, feeling powerful and able to do anything.” -Pope Francis

The Human Genome Project led by Dr. Francis Collins identified some 20,000-25,000 genes spread out among our 46 chromosomes. As more and more genes are identified in human disease, the therapeutic implications are staggering.

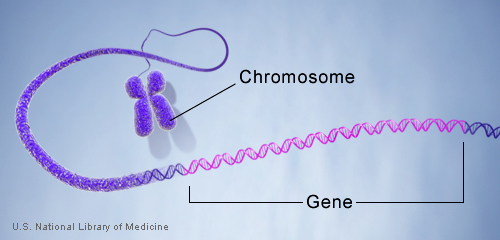

Genes are made up of DNA / Image Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine

Genes are made up of DNA / Image Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine

In neuroscientific research, for example, this technique allows scientists to disrupt gene expression to determine gene function. By using other species (worms, flies, and other mammals), dysfunctional genes have been identified in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

CRISPR can be used to render certain animals sterile: for example, to control the population of malaria-carrying mosquitos and pesky rodents. In more positive applications, CRISPR can be used to prevent the progression of age-related macular degeneration and in the treatment of sickle cell anemia. One company in England is hoping to fix a spliced gene that causes inherited blindness.

Bioethical considerations

With such tremendous possibilities, there are obviously serious bioethical concerns. Fr. Astriaco discusses this at the end of his talk on CRISPR which he gave at the 2019 Conference of the Society of Catholic Scientists. It is worthwhile to listen to all of the distinctions he makes, but the most significant relate to human dignity: one’s intrinsic worth versus extrinsic worth.

The intrinsic value of the human person, made in God’s image, is priceless. The human person has a spiritual dimension that makes us unique in creation. Extrinsic worth, however, is made up of external characteristics, such as wealth and social standing. For the secularist, who denies any intrinsic value based on the spiritual dimension of the person, there is only extrinsic value. So “dignity” depends on the condition or health of the person, hence “death with dignity” language.

Any new therapy needs to be monitored while keeping in mind concerns relating to the dignity of the human person. In the case of CRISPR, it is crucial.

The high calling of the scientist

The technological achievements and advancements of the last 50 years are indeed astonishing. As noted in a previous post, however, there are many ways of knowing and experiencing our existence, whether through the lens of science, philosophy, theology, or psychology.

To understand that science has limits to what it can tell us—or to be cautious in the use of new techniques and technology—in no way denigrates the high calling of the scientist. Maria Montessori captured this calling beautifully in the opening pages of her iconic book, “The Montessori Method.”

“We give the name scientist to the type of man who has felt experiment to be a means guiding him to search out the deep truth of life, to lift a veil from its fascinating secrets, and who, in this pursuit, has felt arising within him a love for the mysteries of nature, so passionate as to annihilate the thought of himself.” -Maria Montessori

Scientists would do well to consider their calling.

For a more complete explanation of the CRISPR editing tool, listen to the TED talk by one of its inventors, Jennifer Doudna.

Read Also:

DNA: A New Kind of Fossil Record