“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.” -St. Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, Chapter 11

This is the second of six in a series. In the first, I discussed how philosophers, Greek and contemporary, viewed time. I’ll recapitulate briefly: one can think of the present as real, and time flowing like a river (“presentism” or “A-theory”), or one can think of “now” as just another coordinate to be designated in an eternal time, as “here” is an index in space (“eternalism” or “B-theory”).

In this article, we’ll focus on three stories of how we perceive time: St. Augustine of Hippo’s thoughts in his “Confessions”; the insights of the American philosopher and psychologist, William James; and what Oliver Sacks, a renowned author and psychiatrist, has to say.

St. Augustine of Hippo: time as a melody

St. Augustine discourses at some length on the nature of time in Book XI of Confessions. Even though he doubts that he can explain what time is (opening quote above), his explanations are insightful—particularly those about the timeless nature of God and how we perceive the passage of time.

In Chapters XXVI and XXVII of Book XI, St. Augustine examines whether duration is a measure of time; he assigns memory as the tool which makes the past real and designates forethought as our way to visualize the future. His discussion focuses on hearing a psalm, and how this example shows how our minds perceive the passage.

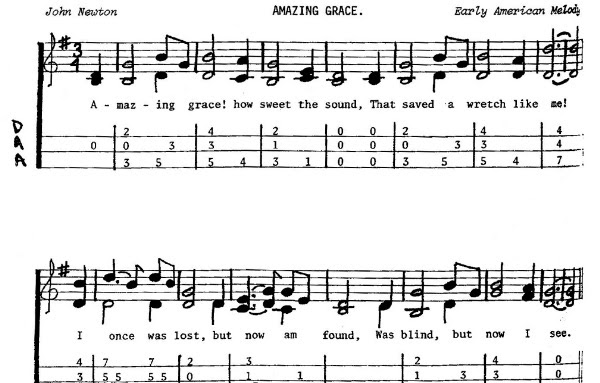

Let me summarize with an example. Suppose you’re listening to music, perhaps a hymn. Listening to one note by itself will not give you the melody. It’s the memory of the previous notes, in sequence, that does so; and it’s the anticipation of the note that is to come that makes the melody memorable.

If we look at the score of Amazing Grace, we see the repetitive AABA pattern (look at the sequence of uppermost notes under “Amazing...sound” “That...me” and “was...see” differing only in the final note). Memory and repetition plays a part in how the melody strikes us. It is a sequence in time, and duration is used to emphasize. Can one imagine all these notes existing simultaneously?

St. Augustine made the point that our perception of time is determined by perception of events in sequence. As with other insights of the wise saint, this view is echoed in contemporary psychology and neurology, as I’ll try to demonstrate below.

William James: the stream of consciousness

William James (1842-1910) was a great American philosopher and psychologist and one of the founders of the philosophical school of Pragmatism. In his seminal work, “The Principles of Psychology,” William James proposed a theory of how we perceive time (Chapter XV).

James dismissed the notion that time is perceived as a sequence of separated, isolated events. This would be “like a glow-worm spark, illuminating the point it immediately covered, but leaving all beyond in total darkness. ” (Chapter XV, The Principles of Psychology.) He emphasized that consciousness of events in the present was linked to memory of events in the past and the expectation of future events:

“...all our concrete states of mind are representations of objects with some amount of complexity. Part of the complexity is the echo of the objects just past, and, in a less degree, perhaps, the foretaste of those just to arrive. Objects fade out of consciousness slowly. If the present thought is of ABCDEFG, the next one will be of BCDEFGH, and the one after that of CDEFGHI—the lingerings of the past dropping successively away, and the incomings of the future making up the loss. These lingerings of old objects, these incomings of new, are the germs of memory and expectation, the retrospective and the prospective sense of time. They give that continuity to consciousness without which it could not be called a stream.” -William James. “The Principles of Psychology, Volume 1, Chapter XV [emphasis added]

According to James, the perceived “present” is not a point in time, but an interval:

“...the practically cognized present is no knife-edge, but a saddle-back, with a certain breadth of its own on which we sit perched, and from which we look in two directions into time. The unit of composition of our perception of time is a duration, with a bow and a stern, as it were—a rearward- and a forward-looking end” -William James. “The Principles of Psychology, Volume 1, Chapter XV

What is the speed of time? James observed that the more events in a given day for us, the faster time passes. Accordingly, we can say that if there were 1000 events during a day, the speed of time would 10,000 times faster (in consciousness) than if there were 1 event in 10 days. (See this nice video about James’s work.) These ideas about the speed of time in consciousness have been developed further by Oliver Sacks, a contemporary psychiatrist.

Oliver Sacks: 'speed,' how slow, how fast we think

In his book, “The River of Consciousness,” Oliver Sacks discussed how fast or slow mental processes can go in normal activities and for disturbed mental states. There are extreme cases when time seems to slow down and when it speeds up. Some of these occur in life-threatening circumstances, some during activities requiring subconscious skills, and some are the result of neurological or psychological disorders. However, all are evidence that the brain sets its own clock.

A man jumps from a high building and his life passes before him. That’s a familiar image, and it’s also a true one. Sacks recounts several stories of how time slows down in such situations: a race car driver thrown 30 feet into the air in a crash experiences his accident calmly, in slow motion:

“It seemed like the whole thing took forever. Everything was in slow motion, and it seemed to me like I was a player on a stage and could see myself tumbling over and over… as though I sat in the stands and saw it all happening… but I was not frightened.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

Time also slows down for good athletes, according to Sacks: training takes over in the subconsciousness while the conscious mind slows down time:

“But at some point the basic skills and their neural representation become so ingrained in the nervous system as to be almost second nature, no longer in need of conscious effort or decision. One level of brain activity may be working automatically, while another, the conscious level, is fashioning a perception of time, a perception which is elastic and can be compressed or expanded.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

A telling example is that of bicyclists in a race:

“In a bicycle race, cyclists may be moving at nearly forty miles per hour, separated only by inches. The situation, to an onlooker, looks precarious in the extreme, and, indeed, the cyclists may be mere milliseconds away from each other. The slightest error might lead to a multiple crash. But to the cyclists themselves, concentrating intensely, everything seems to be moving in relatively slow motion, and there is ample room and time, enough to allow improvisation and intricate maneuverings.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

Neurological and psychological ailments can also affect an individual’s tempo. Tourette’s Syndrome greatly speeds up activity:

“Some people with Tourette’s are able to catch flies on the wing. When I asked one man how he managed this, he said that he had no sense of moving especially fast but rather that, to him, the flies moved slowly.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

Slowing down of time and motion occur in some psychological disorders. A time lapse scan of what seems to be arbitrary, random movements turns out to be a purposeful ordered motion. Sacks talks about a patient with postencephalitic parkinsonism who seemed to be making such motions while sitting outside his office:

“I took a series of twenty or so photographs and stapled them together to make a flick-book… With this, I could see that Miron actually was wiping his nose—but was doing so a thousand times more slowly than normal.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

Psychoactive drugs also change time action and perception. L-dopa can raise the levels of dopamine in the brain and thus accelerate time perspectives that have been slowed down by disease. Sacks relates the story of one such patient, Hester Y, who suffered from postencephalitic parkinsonism, and was treated with L-dopa:

“If she had previously resembled a slow-motion film, or a persistent film frame stuck in the projector, she now gave the impression of a speeded-up film, so much so that my colleagues, looking at a film of Mrs. Y, which I took at the time, insisted that the projector was running too fast.” -Oliver Sacks, “The River of Consciousness”

So we see the speed at which we act and perceive time is governed by our brain, by its memories and neurochemistry. Even so, there are lower and upper limits to this speed. However, as Sacks observes, we can extend those limits by instruments: telescopes to observe over billions of light years from the Big Bang to the present and laser optics to act in nanoseconds.

To Come: 'entropy,' the arrow of time

The next article in this series will deal with entropy, “the arrow of time.” I’ll present, as a preliminary, a mini-tutorial on what thermodynamics is all about.

Read Also:

What is Time? Part One—Philosophy

A Point in Time: Not All Time is Linear

New Ebook Discusses How to Navigate the Weirdness of a Quantum Universe